How could that voice not be heard?

Here is a note from Fereydoun Majlessi about the "Foresight" (Future Vision) project and the book The Voice That Was Not Heard

Fereydoun Majlessi, Sharq, 13 July 2025

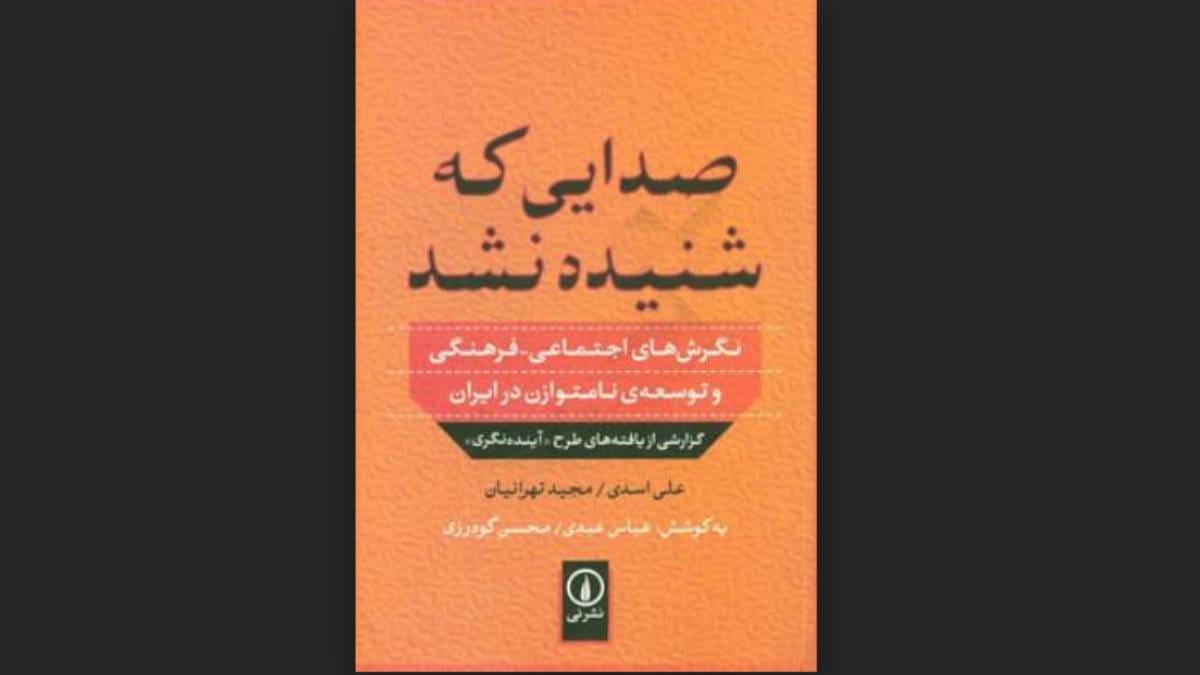

The book The Voice That Wasn’t Heard is a report on the findings of the Foresight project. Written by Ali Asadi and Majid Tehranian, it addresses socio-cultural attitudes and unbalanced development in Iran. Recently, an article titled "Foresight Project: A Voice That Wasn't Heard!" has been circulating on social media, introducing the book.

Shargh Media Group reminds that the book is a report on the findings of the Foresight project. Recently, an article titled "The Future-Looking Project, a Voice That Wasn't Heard!" has been circulating on social media to introduce the book. Fereydoun Majlesi, a writer and former diplomat who experienced the conditions of that time, wrote a note in response to the article. The text states that, in 1975–1976, four years before the 1979 Revolution, an unprecedented project was launched in Iran: the "Future-Looking (Foresight) Project," implemented to understand public opinion. The project was implemented by two of the country’s leading sociologists: Dr. Majid Tehranian, a Harvard graduate, and Dr. Ali Asadi, a Sorbonne graduate.

The project was carried out in collaboration with the Research and Development Center of the National Iranian Radio and Television and took two years. Reza Ghotbi, the director of Radio and Television at the time, agreed to the national "Foresight" project after hearing about it from Dr. Tehranian. It included a national survey, in-depth interviews, and data analysis in collaboration with a group of sociologists at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS). The project was carried out in 23 cities and 52 villages with a large statistical population: 6,000 potential media audience members, 800 cultural and political figures, and 3,000 radio and television employees.

The data analysis was carried out by CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique - National Centre for Scientific Research) mainframes in France, and the results were returned to Iran." The results were astonishing. There was a clear contradiction between public opinion and the Shah’s government's perception of society. People were struggling with cultural divides, educational poverty, political dissatisfaction, and an increasing tendency toward religion." During that time, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi spoke of Iran’s economic growth, its bright future, and its role as a gateway to civilization. However, the Foresight Project showed that economic development alone was insufficient. Society was not culturally or socially prepared for these rapid changes. Only 34 percent of families owned a television, only 45 percent were literate, and 75 percent of men opposed women working outside the home.

Seventy-four percent considered the father, grandfather, and grandmother to be the decision-makers in the family, not the mother. The report concluded that it was a "deeply patriarchal and traditional society." In such an environment, modern television programs did not resonate with society.

Dr. Ali Asadi writes, "Even intellectuals did not connect with the broadcast of the educational program Ballet." More than 23 percent of people thought that cinema should be forbidden. The statistics were shocking: 42 percent did not use the bathroom even once a week; only 9 percent read books regularly; and 32 percent said they did not own a single book. Society was at a critical point in terms of media and cultural literacy."

In such circumstances, religion became a refuge against the wave of modern programs. Ninety-four percent of the people in this study said they prayed, and 79 percent fasted and placed importance on religious practices. The number of mosques in Tehran increased from 700 to 1,140 in three years. Sales of religious books increased from 10 percent to 33 percent. Parviz Nikkhah, a radio and television station director, said, "In modern societies, as development programs accelerate, the number of students decreases. But in Iran, it is the opposite."

He and Hormoz Mehrdad expressed concern about the growth of religious tendencies and public distrust of the system. The Foresight Project found that only 30 percent of the population participated in the parliamentary elections, and 23 percent participated in the local elections. Seventy-seven percent of respondents did not know what the country's problem was. People were deeply alienated from politics. About 90 percent of students considered politicians to be incompetent. Fifty percent of them considered inequality, corruption, and injustice to be the country’s biggest problems. However, the political system did not listen. It even ignored warnings from within the government.

At a meeting attended by the Shah, Konstantin Mozhlomyan, an economist and Armenian deputy head of the Planning and Budget Organization, shouted, "With these things, a revolution will happen. This money will find its footing and come to the streets.” The Shah replied: "I will kick down the door of your organization!" And he did. Tehranian and Asadi warned, "We are caught in unbalanced development."

Rapid economic development without a cultural infrastructure, as well as mistrust, inequality, and traditionalism in society, were grounds for an explosion. However, at a meeting held to present this plan, titled "Shiraz Conference in 1975," the government disregarded the findings of this national research. They dismissed the survey results as "Westernized" and deemed the questionnaire-based study meaningless. From 1974 to 1975, a society emerged that desired economic prosperity and progress. This society was committed to tradition, distanced itself from politics, took refuge in religion, and lacked civil institutions and political parties. The result was a full-scale revolution to transform cultural, economic, and political structures.

Fereydoun Majlessi writes:

The introduction to the book Why Wasn’t This Voice Heard? was excellent. It was consistent with existing facts. It reflected the situation at the time. Alex Mozhlomyan, my esteemed friend, was a calm and gentle economist. He never shouted at the Shah, but he clearly expressed his objection to the costly, inflationary economic policy. It was not heeded!

I also knew Majid Tehranian, who was my sociology and economic development professor during my graduate studies. Their views, especially Mozhlomyan’s, were more related to the economic objections of the late Shah. However, the fundamental problem of Iran was not the 25 percent inflation mentioned in the above note! As experience in the world shows, an uprising resulting from 25 percent inflation and much more can be put to sleep with a machine gun. The cultural and social roots of the revolution are important. The note mentions the cultural and social divide, but the main reason is presented with the general and vague slogan, "the existence of corruption and injustice." The report reflected the current situation but had the following objections:

1) The causes of the situation have been referred to superficially, and most have mistaken the effect for the cause.

2) They did not address the solution to the problem. It is as if they considered proposing the problem sufficient to solve or eliminate it.

3) The report lacked a comparative analysis with surrounding societies, such as Turkey, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Indonesia, Egypt, and Malaysia. Were their cultural status and general literacy better than Iran's? No! Were any of these countries more economically developed than Iran? No! Did religion have less influence and were its rituals performed less frequently among them than in Iran? No! Was social and cultural duality and the resulting gap less pronounced in these countries than in Iran? There was a difference in nature in this regard, so why didn’t the Islamic Revolution happen in those societies?

Iran's efforts toward literacy and cultural development were greater than those of all other countries. Only Turkey was comparable to Iran in this regard. At the time of the Islamic Revolution, 47 percent of Iranians over the age of 15 were literate, and 100 percent of Iranian children attended school and received free meals. In other words, 10 years later, the literacy rate would have completely reversed! As it did. But could that cultural effort have prevented the revolution? It couldn't. The acceleration in economic development, partly due to the Shah's awareness of his limited time and inability to balance it with cultural and social development, led to the Shah's downfall. The report states that the people's inclination toward religious rituals was underdeveloped.

In fact, this tendency existed among the people. The entire non-urban society, and gradually the majority of the urban society with rural roots, felt anger and humiliation towards the modernity or Western-style urbanization of the ruling class. Within modern society itself, revolutionary conflict among the youth and newly literate of that generation had intensified in a Marxist or nationalist fashion and become a sign of prestige, fueling their imagination to benefit from the mass and Islamic revolutionary wave. They rode this wave! Jalal Al-Ahmad, Ali Shariati, and Dariush Shayegan Arshafi were manifestations of the intellectual tension between the city and the countryside, or modernity and ritual tradition. However, the battle led to the victory of tradition, which had no choice but to continue the path of civilization and modernity. Why did Reza Shah's authoritarian modernism have relative success in sending students to school and forming a country out of scattered villages despite causing him to be disliked?

Why did the Shah's accelerated, oil-fueled development program fail, leading to the Islamic Revolution? A hundred years after Reza Shah and fifty years after Mohammad Reza Shah, Mohammed bin Salman's economic and social development programs in Saudi Arabia continue with much greater stability. Despite the lack of political development, the country has a high level of literacy and prosperity. Why is civil development there worthy of attention and respect? And why, despite the similarities with Iran, did the time of revolution in Egypt's conflict between tradition and modernity not lead to a widespread Islamic revolution? These are questions that Majid Tehranian's valuable report from half a century ago does not answer. The Iranian revolution was the result of accelerated industrial development and large population displacements. However, it was also a reaction to Iran's social development surpassing that of its peers, who did not suffer from it. Today, they have also achieved cultural and social development and are waiting to pass the critical phase of political development: freedom and democracy.”